My new favorite artist I stumbled across while on my last trip to Tokyo. His work is all done with a ball point pen and the process and detail in his work in amazing.

Computer Arts Interview –

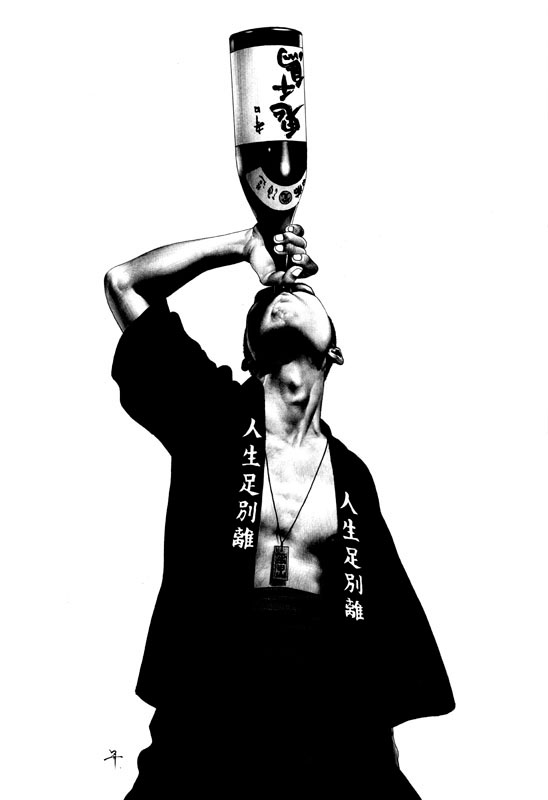

On Shohei Otomo’s website, tucked away behind the visceral and often brutal artwork that he creates, is a self-filmed video of him drawing. The only objects that are in shot are Shohei’s hands, two sheets of paper and a ballpoint pen. From this set-up, he creates some of the most detailed and startling imagery currently coming out of Japan. The video is sped up to double time. Even so, Shohei’s attention to detail and painstaking ballpoint work seems to take an age. He works slowly, but the results, revealed line by line, are mesmerising.

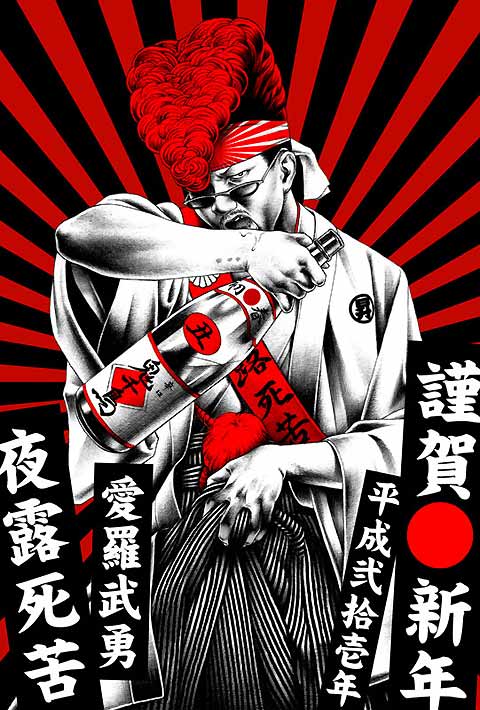

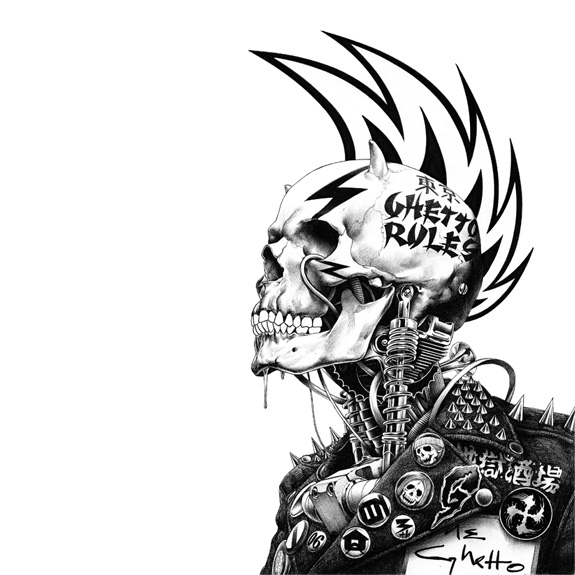

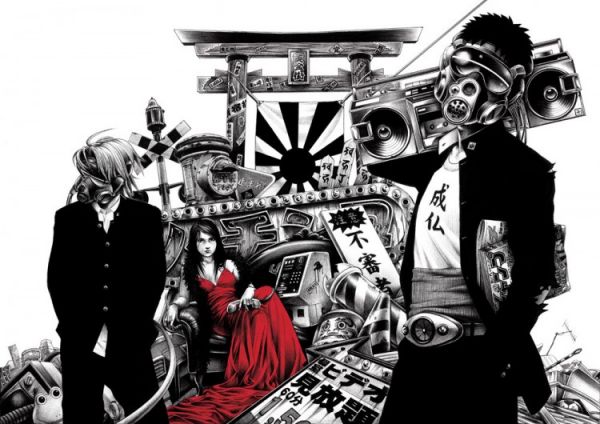

Shohei, who works under the capitalised moniker SHOHEI, was born in Tokyo in 1980, and graduated from Tama Art University with a degree in art, specialising in oil painting. With the oils and canvas discarded, he now creates using ballpoint pens, paper and a fusion of traditional Japanese iconography and twisted, often shocking subjects. Shohei’s artworks often merge conventional character manga with stark sexuality, violence and vulgarity. Yet there’s a deep-rooted humour to his work: geishas wear Bono-esque sunglasses; cherubs hover above a maiden carrying hypodermic syringes; a traditional Samurai coils in fighting position, wielding not a sword, but a heavily painted baseball bat; in another of his pieces, the tip of a severed finger floats in white space contrasted by bright red flashes with the starkness and impact of a twisted Warhol print.

“Back when I was in university, I was just messing around, scribbling stuff on my notebook during my oil painting class,” Shohei recalls. “I wasn’t very good with colours to begin with. I just had more fun drawing with ballpoint – I felt more unrestricted, or free to express myself. Plus I was broke so it was way cheaper than oil painting. When I was 24 I started focusing solely on drawing ballpoint illustrations. I still did oil paintings every now and then, just when I could scrape the money together to pay for all of the supplies,” he continues.

“Back then I was getting a lot of illustration work as a freelancer and working part-time at a convenience store. I designed flyers for my friends’ events and the album covers for their indie bands. I think all my stuff back then was way more hardcore, erotic or grungy. Since my friends’ bands had a similar style and attitude, it worked well.”

While Shohei’s college education taught him traditional Japanese oil painting, his interest and absorption in Western influences and modern Japanese culture explain the conflict his illustrations show. There is a very real sense that his works explore the space where Western culture meets Japanese culture, something that he himself acknowledges.

“I feel Japanese artists create original pieces of work with their natural instincts and overall nimbleness,” explains Shohei. “And they’re very effective at this, but much of what they create is superficial and lacks a sense of depth for me.”

“Western artists on the other hand, tend to take their knowledge of the arts with their solid technical skills and produce very balanced pieces of work, but I have an impression of it being a bit stiff at times. The Japanese use their intuition, whereas Westerners might use their logic more.”

It is this clash of cultural input that defines Shohei’s artwork. There is logic to his process – a very precise, almost painstaking attention to technique and detail that he sees as a Western trait. Yet the results are rooted in contemporary Japanese culture, with obvious reference points and familiar subjects: samurai, geishas, fighting school children and wild-eyed futureshock girls.

This balance is rather notable in Shohei’s creative method, too, while also encompassing many of the traditional techniques used in cartoon – or manga – storyboard creation. After visualising an illustration, Shohei says he then begins planning the piece, and putting a structure in place for the artwork.

“Once I decide what I want to draw, I start sketching out a rough draft with the body movements of the characters, along with wardrobe and prop ideas. I try to draw it out in as much detail as possible until I’m satisfied. I use printed materials, take pictures and even look in the mirror sometimes for reference,” he says.

“Then I take what I have sketched out in the previous stage, and trace it out on an illustration board with a pencil. I then imagine what the end product is going to look like, and start filling in the details with a ballpoint pen. When the details are in, I then take a black marker and fill in the blacks. Once the ink dries, I erase the pencil outline. If there are any imperfections or adjustments that need to be made, then I make those changes and I’m done. That’s my drawing process in a nutshell.”

And what a process it is – simplistic, yet technically detailed, the antithesis of modern, multi-layered digital illustration. It’s also painstakingly slow, yet the precision and detail in his works benefits from this process.

It’s the ballpoint pen technique that Shohei insists makes his artwork so different. After all, the simple colourways and fine detail actually resemble tattoo inking more than they do conventional illustrative artworks.

“When I draw, I can literally feel everything from the tip of the pen all the way to my hands,” says Shohei. “The ink isn’t reflective like the lead tracing of pencils, and best of all it’s cheap! An 80 Yen ballpoint pen lasts me 10 drawings.”

The balance between Western contemporary culture and classic Japanese traditionalism in Shohei’s work has garnered him as much attention abroad as it has in his native land. Several of his shows have been in the United States, where his artworks have proved hugely popular.

“The first show I had was in Kansas City. I was 24,” he says. “In one hour I sold about 20 illustrations, which is insane. I don’t think I’ve sold that many paintings at any of my other shows since. The venue was part of this cluster of art galleries, and it was interesting because there was nobody at any of the other galleries, but my showing was packed! I didn’t know what to expect going into it, but it was probably because they didn’t really have many foreign artists come and show there very often. Having that experience made me want to show my work in the US more. Maybe even move there. But being there for that show, I knew that my work was special because of the Japanese influences I have in my artwork. If I were to move to the States I wouldn’t be inspired to draw Japanese style illustrations. But being inspired to draw something different could be cool too.”

Shohei’s exhibitions in Japan are no less dramatic though. At a recent gallery show in Kanazawa, the organiser asked Shohei to apply his ballpoint technique to human flesh. Using acrylic paint, he created a ‘live’ sketching session, applying make-up and intricate illustrative detail to a model. “It’s actually something that I used to do every now and then,” he admits. “Using some acrylic paint, I just drew some patterns in red, white, and black, inspired by the Kabuki style of make-up (see boxout, left), and created something that would balance out the shape of the model’s body. This show had a pretty decent turnout, maybe 150 people in this small gallery space. It’s rare to have people from Tokyo show their art in Kanazawa, so it turned out really well.”

As well as exhibitions, Shohei has also worked for private clients. While his artworks won’t lend themselves too neatly to mass-market advertising campaigns, they sit in a space where musicians in particular feel an affinity to his style. Like his compatriot, Takashi Murakami, Shohei’s work has found popularity with hip hop and rock outfits, including the post-punk band Japanese Cartoon, which is fronted by renowned hip hop artist Lupe Fiasco. “Lupe Fiasco actually got in touch with me through COMPOUND gallery while I was doing a show there,” explains Shohei. “He was interested in using my artwork. But there wasn’t a lot of time, so I ended up having to use something that I had already completed. So I just trimmed it down a little bit,” he reveals.

When we ask him about his influences, Shohei wears his heart (and his art) on his sleeve. There’s a perceivable cinematic quality to his illustrations, with his characters locked into scenic snapshots. “Kobayashi Masaki’s Seppuku is a favourite of mine,” reveals Shohei when asked which films have influenced his style. “It’s a black-and-white film about a ronin and everything he goes through leading up to his climactic seppuku [a particularly grisly form of ritual suicide by self-disembowelment]. It’s a story about right and wrong, life and death.

“I like Spaghetti Westerns too, especially Sam Pekinpah, director of The Wild Bunch andBring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, my two favourite Westerns. I can’t forget Akira Kurosawa – The Seven Samurai will forever remain a classic – and Toshio Matsumoto’s Shurais great too.”

Shohei finds the way in which characters in Westerns and Yakuza films carry themselves intriguing, and will often be inspired to draw after watching them. “But I don’t have any desire to draw perfect ‘Superman’ characters,” he adds. “We’re just not as interesting without our flaws.”